A day before teeing off for the first round of last fall’s Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals Classic, Charlie Wi plowed through a pile of range balls on the Walt Disney World Resort practice tee in search of answers. Something wasn’t right.

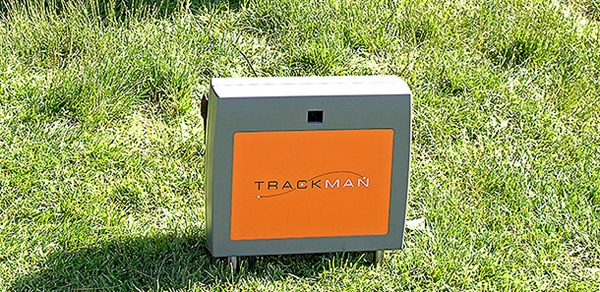

Although his swing felt “normal,” his ball flight was less than perfect, which explained the presence of an orange box looming a few paces behind Wi, instantly sending information to a nearby laptop and creating, at least for Wi and a growing number of similar-minded Tour types, a new reality – a new truth.

“The ball was over-drawing a little bit,” Wi said. “When I got on the TrackMan it showed me my swing plane was a little too far in and out so I needed to change the plane a little. Even without a teacher if you have a TrackMan you can kind of teach yourself.”

The famously meticulous Ben Hogan spent his career searching for golf’s secrets in the Texas turf, while the modern version has shifted his pursuit of perfection to a laptop and enough data to make an MIT graduate go cross-eyed.

TrackMan, a radar device developed by Denmark-based TrackMan A/S, was introduced on Tour about seven years ago initially as a way to pair players with the proper golf ball and club, but it has evolved into a swing panacea for many players and high-profile swing coaches.

Golf, meet data mining.

To be clear, TrackMan has nothing to do with swing theory or teaching methods, it is about facts. The litany of statistics the radar produces isn’t about preconceived notions of the classic swing, just hard undisputed data.

“TrackMan is the greatest teaching tool ever,” said Sean Foley, whose list of Tour players includes world No. 3 Tiger Woods, Justin Rose and Hunter Mahan. “If TrackMan is on when Tiger or Justin are hitting drivers you can see everything. It has been absolutely invaluable.”

TrackMan doesn’t teach the swing – although a growing number of coaches are now incorporating its technology into their lessons – just science.

Consider that the Tour’s ShotLink database now includes a collection of “radar” statistics, a dozen categories that range from the easily understandable “club head speed” to the more arcane “carry efficiency.” With this information coaches and players can easily, and unequivocally, quantify what is and is not working.

“There are a lot of numbers and there are some that are more meaningful than others in diagnosing what a player is doing with his swing, and then there are others that are used to fit a player with a certain driver or iron,” said Grant Waite, a former Tour winner turned swing coach.

For Waite, TrackMan is a constant litmus test that he uses to create a baseline for his players, a list that includes former Masters champion Mike Weir, and track incremental improvements.

“It’s quantifiable data. It gives an ability to say is he improving or is he not? I use TrackMan to measure improvement,” Waite said. “In video, two-dimensional observation, you really couldn’t see that.”

The practical application of TrackMan’s number crunching has quickly, if not somewhat quietly, spread on Tour. Although no small expense – the Tour version retails for over $20,000 – many players have added the device to their regular practice routines.

Charles Howell III, for example, purchased the device in 2012 to diagnose his swing and aid in distance control with his wedges and short irons.

“I first thought it was mainly used for launch and spin,” Howell said. “I learned pretty soon it gives you so much more than that. From angle of attack to launch angle to face alignment.”

Critics dismiss TrackMan’s use as a teaching aid, pointing out the disconnect between cause and effect when dissecting data independent of the swing, and suggest that there is such a thing as too much information.

But that logic means little to radar’s converts.

“If you’re an airline pilot you want to know every instrument on the airplane,” Wi said. “It’s how you utilize them really. You can’t be thinking launch angle when you’re playing, but you have to know how the swing operates so if you’re in trouble you know how to work your way out.”

For Foley the question is not the validity of the information – that, he says, is a question of simple science – so much as it is how the data is applied, or as he suggests the art of teaching.

“Probably eight out of 10 times I give too much information,” Foley admits with a self-deprecating laugh. “For me the key is to go into a lesson and see the numbers and find the simplest way to get the numbers to work. You have to be efficient and use the most minimal amount of information.”

That, however, has nothing to do with the validity of the information or its place in modern teaching. A notion that is backed up by the fact that more than 30 Tour players currently own their own TrackMan and there is often a line of the circuit’s best and brightest waiting to use the machine on Wednesdays at Tour stops.

By itself, the player that led the “carry efficiency” category in 2012 on Tour, hint he works with Foley and is not named Woods or Rose, means little. But combined with the other elements of instruction it is a telling number when success is measured in a fraction of a second.

“It’s not going to tell you what you need to do or what you need to fix, but it tells you if you need to shallow out the swing or maintain your spine angle,” Foley said. “If you’re not using it in 2013 you’re behind the eight ball. New drivers are made with science, not art.”

Hogan once reckoned, as only the Hawk could, that if you hit 1 million golf balls your 1,000,001st attempt would be better than your first. It seems that number, thanks to TrackMan, has been dramatically reduced.

By Rex Hoggard