When Pinnell looks back on his time together with Zhang thus far, there’s one story that jumps to the forefront of his mind. It was during a junior tournament in the 2020 PING Invitational. Zhang opened with a two-under 70, but had just shot 75 in her second round—an unusually high round for a phenom who by that point was already destined for big things in women’s golf. But it wasn’t the score that surprised him most. Rather, what happened after.

“I got a text from her, which was very unusual, all it said was: ‘It was brutal out there today. The wind was up a little bit and it was overcast and cool, and I had a swing flaw,'” Pinnell said.

“I dang near fell out of my chair when she told me, because she never calls or texts me about her golf swing on the road … I was wondering how in the heck she’s going to get her swing back into shape when she does have an issue.”

The next day Zhang shot 67 and won. A week later she returned to Pinnell’s driving range. Pinnell says ordinarily, he keeps his role simple: To give specific answers to specific questions. But that text was so unusual, it had him wondering: What changed between rounds two and three? From a swing-flawed round to a tournament-winning one?

“She said, ‘Well, I went to the driving range right after my round and I took out my 9 iron. I didn’t hit one ball. I went through all the golf swing fundamentals one by one making really slow swings. And in less than 10 minutes I found it and I knew what it was. I took my club, I put it back in my bag and I said, ‘Dad, let’s go have dinner.'”

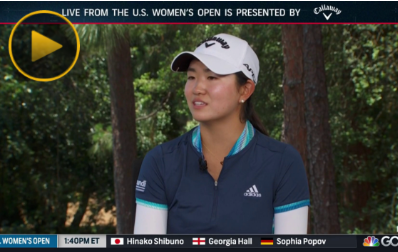

It’s Rose Zhang’s golf swing that has captured the adulation of the golf world. Soft like warm butter, but seamless like a second hand moving around an expensive watch.It sparkled once again during a practice round at the U.S. Women’s Open this week, when a viral video showed Zhang flipping an effortless wedge into Pebble Beach’s iconic seventh hole and then the tee she used into her pocket.

But as impressive as her golf swing technique is, Pinnell has seen plenty of great swings over the years. It goes with the territory, being a good golf coach near a hub in Southern California. For Pinnell the ultimate validation as a coach is helping a student understand how their golf golf swing works—their habits, both good and bad. The technical work is done at home, on the driving range. On the course, or during tournaments, is when the self-starters thrive. A separate, but equally essential skill.

To master that, it’s not about observing the golf swing itself, but understanding the basic principles that make it all work.

Grip tweaks for clubface awareness

Pinnell likes to say he doesn’t instruct students but rather helps them “build golf swings,” which he defines as “delivering the club into the ball in an efficient manner.” The pair will use launch monitors to track this, and lean heavily on V1 video software to check some key points in Rose’s golf swing.

Ultimately though, there’s one connection between swing and club: Through the hands.

Zhang’s grip may not look different from day-to-day to the rest of us, but Zhang is constantly making little adjustments, Pinnell says, to match up with the slight changes in the rest of her body. That’s the thing about golf swings. They move around. Making these sometimes imperceptible grip changes allows rose to calibrate her hands with the clubface, and understand where it is during the crucial moments of impact. It gives her a sense of clubface awareness that is present in every great golf swing.

“Oftentimes when she says that she feels like her grip is off, I will look at it and it looks really good, but she doesn’t feel comfortable. So we’ll mess around with it just a little bit and all of a sudden she’ll say, ‘Oh, this is better. Let me hit a ball’” So she’ll hit a ball and say, “That’s it. I’ve got it now,’” he says. “I don’t even know what we did. We just moved her hands just a little bit because you can’t see it. The feeling is so dialed in that you can’t see something that is wrong, but you can feel it.”

On the downswing, Pinnell says maintaining that width prevents the club from getting disconnected from the rest of her body—into a prototypically “stuck” position—which helps release more energy back out into the clubhead.

“That width in her takeaway gives her golf swing that structure. There’s no slack in it, no looseness,” Pinnell says.

“We monitor the kinematic sequence on V1 pretty intensely, but the club first on the takeaway starts the movement of the arms; the arms will start the turning of the shoulders and the backswing; and then the shoulders will initiate the hip turn. We really like the top where the arms are out in front of their chest and really wide. A lot of the faults today in players that come in that are really pretty good players is they let their right elbow swing around, beside them where it’s disconnected from the right shoulder.”

Structure first, not speed

Pinnell’s most controversial opinion is refuting the popularized idea that junior golfers should chase speed before technique. Those who endorse that idea argue that building your golf muscles is easier the younger you are. Backswing technique can be fixed relatively easily, they say. Adding speed only gets more difficult, the older you get.

Pinnell understands their point, but simply disagrees.

“I’m really in the minority of coaches that believe today you should be teaching the kids how to hit it as far as they can. There’s 95% of the guys and girls out there that are coaching to hit the ball hard,” he says.

“Of course, we’ll try to add some speed when we get a little older. But I think once you get someone who is swinging hard, it’s going to be harder to get them in the positions that will actually help them be able to hit the ball where they’re aiming,” he says. “It’s having a Corvette and it’ll go 200 miles an hour. Well, you don’t want to always have your foot on the pedal at 200 miles an hour because you’re going to wreck it. I’d rather have the swing built and then have them use whatever speed they have in their body within that.”

Moving into your left side

Pinnell says lots of golfers struggle with the second of those two moves. They load back, but they never make it to their lead side. It’s the byproduct of the modern era, Pinnell says, where players hang back on their right side in an attempt to hit more up on the golf ball.

On the rare occasion Zhang struggles, that’s often what happens.

“Sometimes we have a little bit of a problem getting into that left side, because a lot of players today are hitting off of their right side,” he says. “We like to see everything get over on the left side.”

For Zhang, the feeling of getting into her left side is intertwined with her tempo. Too fast and she can tend to hang back. Smoothness as she transitions from backswing to downswing helps her move into her left leg, and swing through.

This was actually one of the first things Zhang and Pinnell worked on together. The 11 year-old’s golf swing was in good shape when she arrived — thank her father for that, Pinnell says — but the sequence of moving into her left side was slightly off, he says.

“The motion that she had was pretty good, it just wasn’t synchronized as well as it could be and she was out of position in some of her moves, so that’s where we started” he says. “I knew there was some potential there. We just didn’t know how far it was going to go.”